By Liz Bowles, CEO, Farm Carbon Toolkit

Every five years, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC)1 publishes a statutory report detailing the UK’s ‘carbon budget’ for a future five-year period. The 7th Carbon Budget covers the period 2038-2042. It is a stock-take of UK GHG emissions (current and future) and provides advice to the Government on how and where these emissions will need to be reduced (‘the pathway’) if the UK is to meet its legal obligations to reduce emissions to net zero by 2050.

This report came out with other reports and consultations such as the Defra Land Use Framework Consultation and the IGD’s Net Zero Transition Plan for the UK Food System. Certainly how we produce food and look after agricultural land in the UK is coming more and more under the spotlight.

Within the 7th Carbon Budget report, it is good to see that the role of land use change in removing carbon is now being linked to agricultural land which gives a truer picture than was previously the case, when land use change was in a separate silo.

It is clear that the carbon budget is very high level, focussing on climate impacts only, with little reference to the impacts of the proposed changes on biodiversity across the UK’s agricultural land. In reviewing this budget, FCT has taken a very practical viewpoint and has reflected on areas where the budget could have helpfully provided more detail and looked at how to fully engage with farmers and growers across the land who are on the delivery frontline.

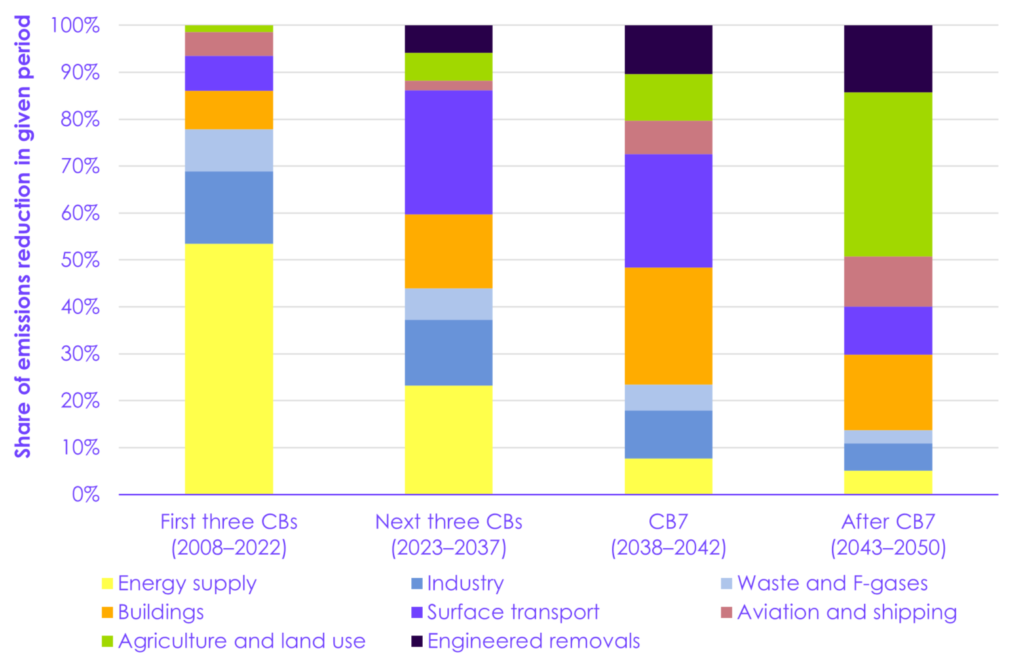

As other sectors decarbonise, the proportion of total emissions arising from agriculture will increase, putting more pressure on the sector to make progress on emissions reduction and carbon removals. In 2022 the contribution of agriculture to overall UK emissions was 12%. By 2040 this is predicted to rise to 27%, after the activity to reduce emissions set out in the carbon budget and it will be the second highest emitter after aviation even with the target action outlined in this carbon budget.

The report proposes a pathway for agriculture to reach net zero by 2050. Not surprisingly woodland creation, peatland restoration and other land use changes are highlighted as mechanisms to sequester more carbon. There is significant reliance on carbon sequestration into land sinks through the 2040’s but little reliance on any level of carbon sequestration into soil itself.

There is a reliance on increased tree planting from the late 2020’s onwards as trees will only start to sequester larger volumes of carbon from 15 years of age onwards. According to the UK Woodland Carbon Code, sequestration rates for woodland increase dramatically during the “teenage years” of woodland establishment. In total, woodland creation has been modelled to contribute 15% to emissions reduction by 2050 . This will require an additional 1.1 million ha of woodland to be planted by 2050. In addition some 300,000 ha of lowland peat and 970,000 ha of upland peat will be returned to natural/ rewetted condition by the same time.

For agriculture the reduction in overall GHG emissions is targeted at 45% by 2050 compared to 2022, coming primarily from a reduction in livestock numbers (38% by 2050) with a relatively small contribution from the adoption of low carbon farming practices. These reductions are significant, reducing the breeding flock of sheep from 15 to 11 million ewes and the breeding cattle herd from 3 to 2 million head.

The reduction in grazing livestock numbers will release land for tree planting. The combined effect of the changes to farming practice and tree planting is to suggest that the sector will become a net sequesterer of carbon by 2048.

There are a number of important assumptions included within this budget which bear further scrutiny:

- Crop yields will increase by 16% by 2050. Presumably this increase is deemed necessary to ensure adequate plant based foods to replace the current levels of meat in our diets. However it is questionable whether this will be achievable in practice, even if gene editing technologies are successful and fully deployed as more adverse weather events are already affecting yield levels in the UK and across the world. It is not clear how critical to successful achievement of the overall plan this is.

- Stocking rates for grazing livestock on lowland will increase by around 10% with stocking rates in the upland reduced. Presumably the former is to allow for more land to be released to grow crops for human consumption and the latter to reflect the current over-grazing in parts of the upland and to reflect rewetting of upland peatlands and the proposals for tree planting. Targeting increased stocking rates for lowland livestock could require additional artificial fertiliser inputs which would seem counter intuitive, though the increased stocking rate could potentially be achieved through improvements in grassland utilisation efficiency.

- Consumption of meat products (primarily beef and lamb) will fall by 35% by 2050 compared to 2019 levels. On first sight it would appear that changes in consumption are mirroring proposed reductions in livestock numbers, however, no mention is made of any changes in dairy cow numbers, but since the majority of beef produced in the UK comes from the dairy herd this will also impact milk production. Consideration is also given to replacing meat in ready meals with plant based alternatives which will negatively affect carcass balance, with lower value “cuts” often used for this purpose at the moment. This would put further pressure on sector profitability. The targeted reduction in ruminant livestock numbers would lead to a lower requirement of permanent grassland for grazing of a similar order to the reduction in livestock numbers. This would amount to around 3 million ha which could be diverted for other use, where this is possible. Tree planting would be a key use for poorer quality ground (topography and stoniness) with better quality grassland moving to arable cropping where this is possible. This would probably lead to loss of carbon from soils, especially when permanent grassland is first transitioned to arable cropping2. It is not clear whether this has been accounted for within the overall budget.

- The carbon budget includes a very low value (0.5Mt CO2e per year for carbon removed by grassland soils). This appears to be low and seems to take little account of the ability for well-managed livestock systems to bring multiple benefits beyond reducing emissions including carbon removals into soils and enhanced biodiversity.

More research and data analysis is required urgently to inform us of the ability of the soil to permanently and reliably store more carbon and how best this can be done. We have some information as do others, but as yet this is not a body of evidence which the CCC can use as part of its carbon budget. - Returning around 300,000 ha lowland peat to a rewetted state will impinge upon its current use for growing vegetables, fruit and arable crops. The report does mention that some 10% of horticultural production will move indoors, which is likely to focus on leafy salad type crops. However for field scale vegetable production left to be grown outdoors the question remains as to where they will be grown. Moving vegetable growing to other parts of the UK will require careful site selection if current levels of margin (currently pretty low) are to be maintained and consideration of the infrastructure required, such as pack houses and cold stores.

There were also a number of notable omissions from the budget:

- Whilst the pathway to reduce nitrous oxide emissions are recognised as coming primarily from agriculture, there is no mention of the need to reduce reliance on fossil fuel based N fertilisers. For arable cropping, up to 75% of total emissions arise from the production and use of artificial N fertiliser. Great work is being done to produce low carbon alternatives, but further information on the likely “winning technologies” in this space would have been helpful.

- The level of efficiency of the UK to produce food at a lower GHG intensity than some other nations, utilising fewer arable resources (land and feed) and with lower supply chain discards through a circular feed system provides the nation with a competitive advantage in terms of overall emissions per unit of home grown food. This could be better recognised within the budget report.

- There is no mention of any target to reduce numbers of pigs and poultry within this 7th Carbon Budget. Whilst the animals themselves do not emit methane, their manures do and their reliance on imported soya has a significant impact on overall UK agriculture emissions as well as the soil degradation associated with cereal production to grow the cereals they wholly rely on. We have estimated that reducing reliance on imported soya by 50% and moving to feeding UK grown beans and pulses will reduce the emissions from agriculture by 7% (primarily due to reduced reliance on artificial N fertiliser and to removing deforestation emissions on 50% soya supply).

Reliance on land use change to enable agriculture to reach net zero by 2050

In the period from 2043-2050 agriculture and land use are budgeted to contribute the largest share of net emissions reduction (35%) – see figure 2 below from the Carbon Budget report, and to reach net zero emissions by 2050 as a result of increases in carbon sequestration into land sinks (primarily increased areas of woodland and reduced emissions from peatland due to changed management) with emissions of around 25Mt CO2e and sequestration of around 26Mt CO2e per year. Current emissions from UK agriculture are around 48Mt CO2e per year.

At FCT, we are in agreement with the Agriculture Advisory Group of the UK Climate Change Committee and its report in calling for more nuanced targets which better reflect the benefits of UK livestock production, especially when it is primarily based on the consumption of forages. We also agree with their view that it is important to reflect on the impact of the different gases on warming aligned to the Paris Agreement temperature goal. Both GWP100 and GWP* metrics are important and could already be reported in concert to inform on both GHG accounting (CO2e) for national inventories and impact of different GHGs on climate warming (CO2e) important for the Paris Agreement.

We believe that the report could be much more positive about the contribution that resilient farming businesses, agricultural land and farmers can make to meeting the climate change challenge. Positive engagement and empowerment of farmers, growers and land managers are critical elements in building confidence and encouraging investment but is currently patchy, with beacons of good practice such as the Farm Net Zero project in Cornwall, which is delivering change on the ground and practically supporting farm businesses to transition towards net zero.

Footnotes

- A body set up to hold the government to account on their progress towards net zero and reducing emissions

- The UK GHG inventory suggests that the average change in non- organic soil carbon density (to 1M deep) from converting grassland to cropland in England is -24 tonnes C/ ha, in Scotland is -101 tC/ha, Wales -39 tC/ha and NI -68 tC/ha