Why Care About Carbon as a Farmer?

In recent years, there has been a rise of interest in carbon across the globe. But why should you, as a farmer, care about this? At Farm Carbon Toolkit (FCT), we think there are several important reasons for farmers to care about carbon. These range from economic benefits to the important role farmers play in delivering solutions to climate change and acting as stewards of the land, providing future generations with productive and sustainable farms.

We believe that caring about carbon can:

1. Have many economic benefits

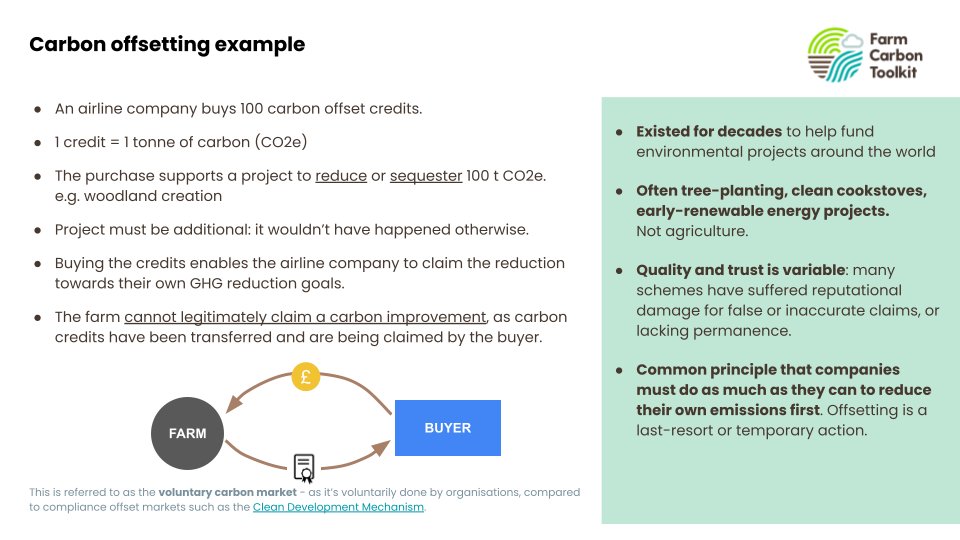

Reducing farm-based emissions is generally good for the bank balance! For example, high carbon footprint items are frequently associated with a high economic cost; by reducing your carbon emissions you can often reduce costs. Caring about carbon can also give rise to new business opportunities, with sustainability incentives from governments and organisations becoming more and more common.

2. Improve soil health

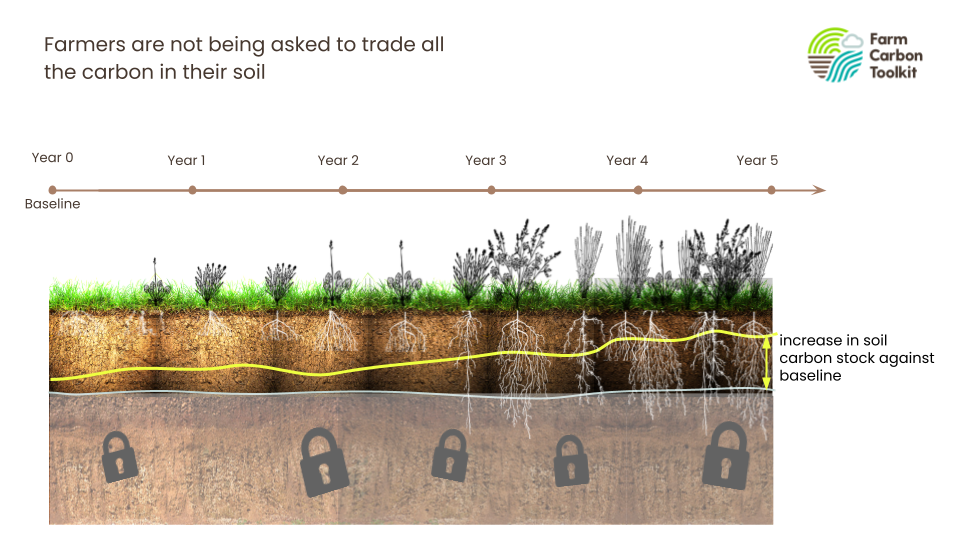

Implementing practices that increase the amount of carbon stored in soils can improve the health of your soil. Soil carbon acts as an important fuel for beneficial soil microbes that supply your crops with the essential nutrients they need to grow. By creating healthier soils, you achieve higher crop yields for the same (or fewer!) inputs, making your land more productive and profitable. Improving soil health helps preserve the health and fertility of your land for future generations.

3. Highlight inefficiencies on farm

We find that carrying out a carbon audit can often act as a useful management tool, helping farmers to spot any wasteful activities currently happening on farm. Items associated with high carbon emissions are typically associated with a high price tag; taking steps to improve any inefficiencies discovered helps to improve your farm’s finances as well as reducing your carbon footprint.

4. Improve farm resilience

The climate crisis causes many of the issues that farmers are currently facing across the globe. By adopting carbon management practices, you increase the farm’s resilience to:

- Local climate change impacts (droughts, floods, heatwaves and other unpredictable or extreme weather events).

- Price fluctuations of inputs.

- Unpredictable policy changes.

- Changing markets for products.

5. Help farmers play a major role in combatting climate change

Given agriculture is the main producer of methane and nitrous oxide emissions, some farmers may feel a sense of responsibility to address this. The good news is that agriculture can be a major part of the solution! Farmers can have a big impact by reducing their emissions and can even help to absorb emissions from the atmosphere. This can help the global efforts to combat climate change whilst ensuring the sustainability of your own operations.

6. Help your country meet climate change commitments

The UK, for example, has legal commitments to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. It is likely to become increasingly important for landowners and businesses to evidence actions taken to reduce carbon emissions. To do this, carbon audits will be required. Understanding your carbon emissions now can help you stay ahead of any future government regulations that may request the monitoring and reduction of carbon emissions.

7. Help supply chains meet climate change commitments

Due to citizens, businesses and governments increasingly favouring low-carbon food, many supply chains are also striving to meet net zero emissions. Supply chains will therefore be looking for farm suppliers that are taking steps to reduce their carbon footprints. Some merchants, cooperatives and aggregators may even offer incentives to encourage their suppliers to have carbon audits and take action to reduce their carbon footprints. Carbon footprinting is now becoming a marketing angle for many products; farmers who demonstrate a commitment to carrying out carbon audits and reducing their carbon footprint may therefore benefit from higher market demands for their low-carbon products.

8. Empower farmers to engage with the wider public

Carbon is a measurable metric that can be used to demonstrate change over time. This can enable a positive narrative and improve public perception of the role of agriculture in climate change. With customers showing an increased interest in the carbon footprints of their products, farmers have the opportunity to share what agriculture is doing to reduce its impact on the environment, helping consumers understand the hard work that goes into their food.

9. Help support biodiversity

Your farm is in a unique position to promote biodiversity and create habitats for wildlife. Diverse ecosystems can provide your farm with many benefits such as improved soil health, natural pest control, natural disease regulation, pollination and improved climate resilience. These benefits play a role in preserving the health and fertility of your land for future generations. Supporting biodiversity is also a fantastic way to engage your community and the general public; biodiversity can connect individuals to the natural world, enhance personal well-being and be beautiful to observe.

To summarise, taking steps to improve soil health and reframe management decisions through a carbon lens can help your farm to improve its resilience, future proof harvests, mitigate climate change and engage the public- all whilst enhancing profit margins.

FCT’s Role in Your Carbon Journey

We believe that caring about carbon and taking steps to improve carbon footprints is a journey with no defined end point. There will always be something more you can do to reduce your emissions or increase sequestration. We know this can seem daunting and overwhelming, but it can also be an exciting and inspiring opportunity for farmers.

At FCT, we are here to meet and support you wherever you are in your carbon journey. It doesn’t matter to us if you are right at the start of your journey or have already come a long way; any steps taken on your carbon journey should be celebrated- it’s extremely valuable work!

FCT enables you to measure carbon footprints using the Farm Carbon Calculator and points you towards potential solutions, advice and inspirational events. We are in a unique position to offer independent support and advice to farmers– our staff members don’t receive commissions for farmers carrying out carbon audits or reducing their carbon footprints! Our small but growing team of committed staff are simply passionate about food, farming and supporting farmers to make a positive difference.

Our Vision

Our vision is a farming sector that minimises its carbon emissions and maximises its carbon sequestration, whilst producing quality food and a wide range of public goods, all produced by resilient and profitable farm businesses.

Its all too easy to forget the crucial part that we as farmers play in creating a profitable industry that can be sustained long term and investing in skills and people development can help businesses to grow.

Its all too easy to forget the crucial part that we as farmers play in creating a profitable industry that can be sustained long term and investing in skills and people development can help businesses to grow. The lifeblood of any business is the workforce – finding skilled and committed workers can be a challenge for any business, but especially on farms. There is a shortage of younger entrants to the farming industry,

The lifeblood of any business is the workforce – finding skilled and committed workers can be a challenge for any business, but especially on farms. There is a shortage of younger entrants to the farming industry,

Recent Comments