In May 2024, the Farm Carbon Toolkit were delighted to hold a farm walk at Lockerley Estate in Hampshire, home to one of the finalists from our 2023 competition. We would like to thank the Estate Manager Craig Livingstone and one of the owners Sarah Butler- Sloss for being so generous in hosting the farm walk.

Everyone who attended the farm walk heard from Craig and his team on how he has managed to make significant reductions in business greenhouse gas emissions, enhance the farmland biodiversity and enhance business performance.

Introduction

Craig Livingstone took on the role of farm manager at Lockerley Estate, owned by the Sainsbury family, 9 years ago with the challenge to improve biodiversity, sequester carbon, increase the health of the soil, and make a profit. To achieve this, a mission statement was devised with a list of objectives that really helps the whole estate team to work collaboratively to achieve the farm’s goals.

With just under 2,000 ha in Stockbridge, Hampshire, Craig farms Lockerley Estate and Preston Farms as one, which includes arable, grassland, woodland, a veg shed, and pockets of countryside stewardship schemes and SFI options. The farm is also part of a joint venture sheep and cattle enterprise, gaining benefits from grazing and muck which is integrated into the arable rotation.

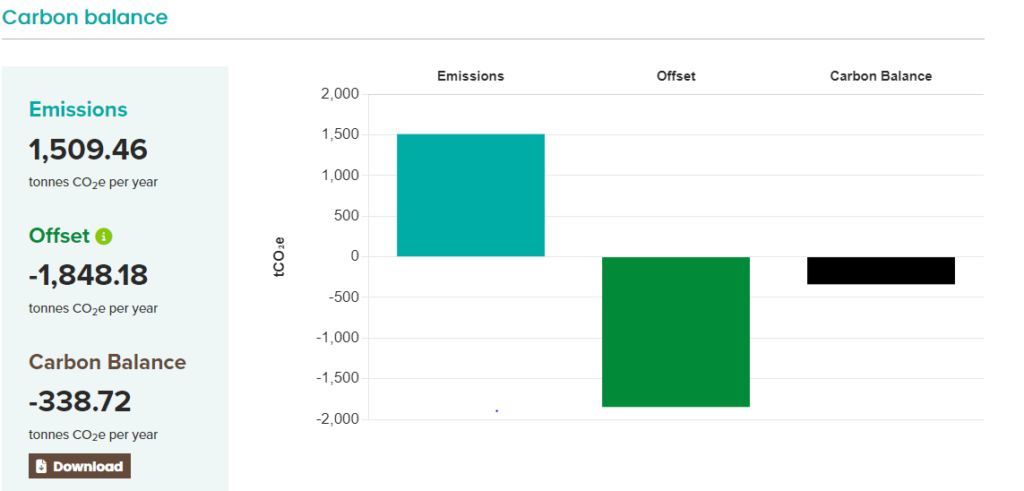

Over 9 years, Craig and his team have managed to vastly reduce emissions by transitioning to zero till and reducing artificial fertiliser and chemicals by broadening the rotation and integrating livestock. Specifically, Craig has saved 56,000 litres of red diesel annually and reduced pesticides and N-based fertilisers by 46% and 53% respectively. Soil organic matter has also increased by 1.1%.

Despite focusing on biodiversity, carbon and soils, Craig’s number one priority is profit – every hectare must pay for itself. Where he can, countryside stewardship schemes have been stacked with SFI options to increase profits. In some cases, the options available have encouraged Craig to adopt techniques that, for example, provide integrated pest management because the overall payment in combination with reduced pesticides is more than the potential loss in yield.

Currently, there has been a 17% change in land use, however the farm is still producing 9,000t food (approx. 4.5t/ha). So how has Craig managed to take the farm and reduce its emissions and increase soil organic matter?

Here are some of the highlights from the walk:

Arable

Using a broad and diverse rotation and choosing varieties that require fewer inputs, Craig has managed to halve the farm’s emissions due to vast reductions in fertiliser and pesticides. This in part has been achieved through implementing a mixture of winter and spring cropping interspersed with diverse mixes of cover and catch crops; legumes such as peas and beans; rotating grasses and legume fallow. The farm is also experimenting with clover understories and poly-cropping, prioritising diversity to build fertility and maintaining cover and living roots in the soil at all times.

The farm’s transition to no-till, aided by a zero-tillage seed drill, has also resulted in improved soil health and structure, increasing porosity and facilitating better water infiltration and enhanced soil biological activity through less disturbance. A multi-pronged approach to reducing fuels and fertiliser usage.

Encouraging diversity

As mentioned, the farm has taken advantage of environmental schemes such as winter bird feed (AB9), flower-rich margins and plots (AB8), and nectar flower mix (AB1) for multiple reasons. In short, to connect the woodland and encourage a host of wildlife, provide integrated pest management, and to make land more profitable.

Perhaps most interestingly, the team have implemented 6m assist strips of AB8 within a select few arable fields to encourage pollinators, beneficial insects, and predators. The initial cost of the seed is expensive; however, in this instance, the farm is not looking to reseed any time soon (especially within the duration of the agreement). That combined with savings on pesticides, they have found it far outweighs the cost of seed – it makes business sense.

Craig has also looked critically at areas that are susceptible to weeds, difficult to graze, areas where the land lies wet, or where the shape of the field is awkward. Here, he has taken land out of production and implemented AB1 or other schemes to benefit wildlife and pocket.

Composting

A big project on the farm is taking cattle FYM and producing a superior product in solid compost and liquid extract using the Johnson-Su methodology. Agricultural soils tend to be bacterially dominated through repeated cultivations and chemical inputs but this process favours fungal communities which are excellent at cycling nutrients, disease suppression and soil aggregation.

Good quality cattle muck is mixed with clover bales, straw, and woodchip, and through a series of steps breaks down into a fungally dominated compost.

Once ready, a compost tea is created by placing a mesh bag full of compost into an IBC of water which is left to steep. This produces a highly nutritious and microbially active substrate which can easily be spread during drilling (rip and drip) and goes a lot further than the compost itself as well as reducing reliance on bagged fertiliser.

Veg Shed

Set up three years ago with a strong commitment to benefitting health, community, and the local environment. The veg shed is made up of 2 acres, 3 polytunnels, 40 laying hens and a fruit cage. The garden grows 50 different fruits and vegetables which it sells to local businesses on a wholesale basis but mostly through a local veg box delivery service.

Everything is grown from seed using heritage and heirloom varieties which have more diversity, and from testing, seem to have more nutritional value. They are also more resilient to a changing climate responding better to drought and high rainfall and requiring less inputs than other high yielding varieties.

The garden is designed as a polyculture and receives no artificial inputs, instead utilising compost from the farm and enlisting the help of dynamic accumulators to extract and release nutrients from the soil.

Wood pasture and Woodland

Linking SSSI woodland and calcareous grassland, the farm took advantage of the woodland pasture creation scheme and introduced longhorn cattle to graze instead of taking silage and hay. The aim is to create a large grazing area of species rich grassland and wood pasture that joins with 220ha of woodland improvement.

There is over 300ha of woodland at Lockerley Estate including a portion of semi-natural ancient woodland. The improved woodland is periodically thinned whilst retaining canopy cover to maintain diversity. Timber is harvested and removed with a percentage of profits returned to the estate.

The biggest outcome has been the flourishing biodiversity and wildlife. Diverse grassland is growing out from the hedges and wildflowers are starting to recover, blending into the woodland, and creating a mosaic landscape. Bird surveys see an increase in species year on year and botanical, butterfly and grasshopper surveys with fixed point photography are ongoing.

Hedgerows

Last but not least, Lockerley Estate takes great pride in its hedgerows, planting 12,000 hedgerow plants in the last year. Cutting regimes have also been lengthened to support all wildlife, from insects to birds to small mammals. This is made possible by replacing the hedge cutter with a saw blade to accommodate the thicker branches; the trimmings are then used for ramial woodchip in the composting process.

Summing up

Overall, it was a thoroughly enjoyable day and an interesting insight into how Craig and the team manage to maintain a balance between a thriving farm both in terms of biodiversity and bottom line productivity. Craig has demonstrated that economic resilience can go hand in hand with reduced inputs and tillage without compromising on food production. Entries to this year’s Carbon Farmer of the Year competition close on the 14th June, so if you believe you are reducing on farm greenhouse gas emissions do enter our competition here

Recent Comments