By Joe Jones, FCT Farm Carbon and Soils Assistant

For many, views of animals grazing under large trees invokes the image of a slower pace associated with older farming periods. Whilst few would dispute the beauty of this, modern agriculture has largely forgotten the utility of trees in farming systems, often seeing them purely as a refuge for wildlife and a nuisance to farming activities . But the work of Dr Lindsay Whistance, Senior Livestock Researcher at the Organic Researcher Centre, is seeking to provide farmers with evidence of how valuable trees are in both environmental and economic terms. Trees can support greater animal welfare and more resilient farm enterprises overall. In this case study, we look at some of Dr Whistance’s research, which examines some of the ways trees positively contribute to livestock farming systems.

Trees on Farms through the Ages

In the past, trees in both hedgerows and fields were much more integrated features of the British farming landscape. Farm trees, hedgerows and woodland were managed carefully to produce a variety of resources. These included raw materials for many household items and crafts, timber for buildings, fuel, as well as fodder and shelter for farm animals.

As the value of wood declined, alongside the adoption of more mechanised and larger scale agriculture, the use for trees on farms diminished. Consequently, many farmland hedgerows and trees were removed in the last century to increase efficiency and productivity. The decline of trees in the farming landscape meant many benefits were lost, some which were noted and others which are only becoming more apparent now.

The Benefits Triage

Trying to understand and put meaningful data behind what these benefits might be has been a key component of Dr Whistance’s research. She has helped identify several key areas, both directly and indirectly, where trees positively contribute to livestock welfare and has provided a strong case for their inclusion in farming systems.

1. Shelter – buffering the extremes

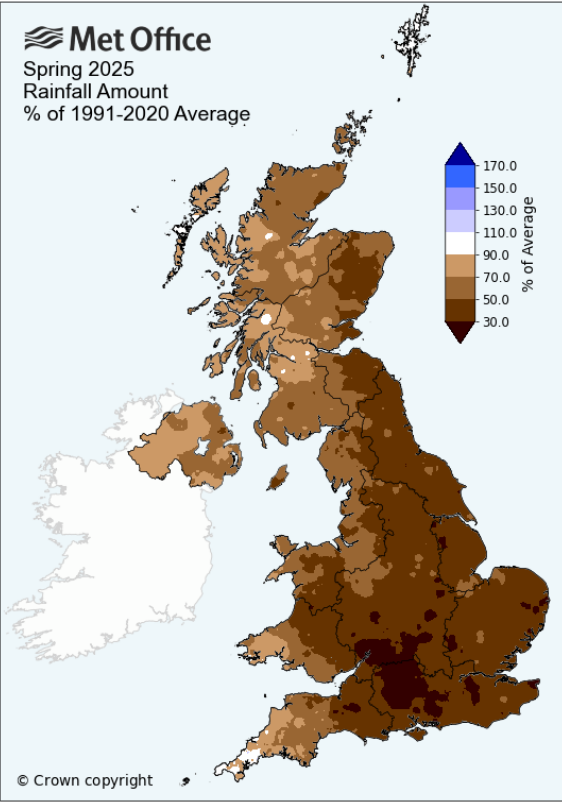

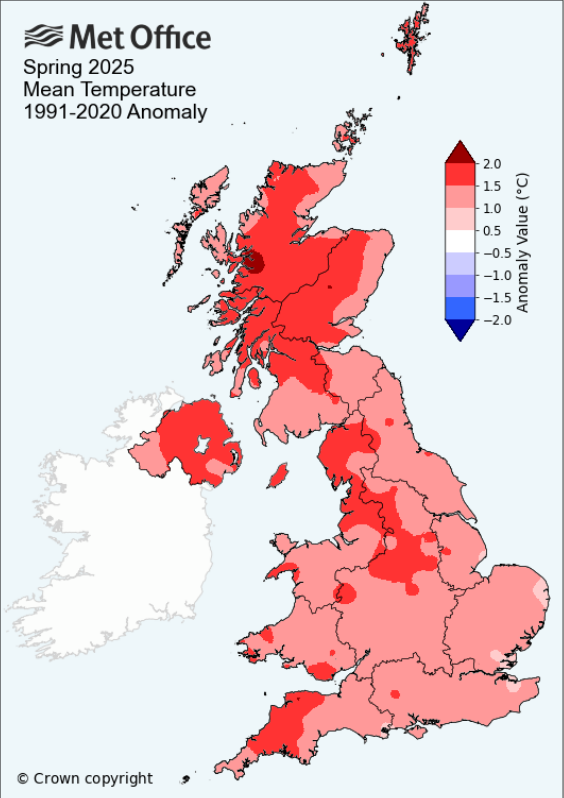

One of the key challenges farmers face now is the increasing extremes of climatic events. Extreme heat, cold, wind and rain are all challenges to livestock who cannot access places to take refuge. Animals maintain a ‘thermal comfort zone’ where bodily processes are regulated. When temperatures move beyond this zone, the animal begins to experience stress which leads to a greater susceptibility for illness or death.

In hot environments, where animals’ body temperature exceeds the higher critical temperature (HCT), animal food intake decreases in an attempt to reduce heat load. An example of this is in dairy cows, where heat stress leads to a negative energy balance, increases metabolic disorders, and decreases milk production. FCT’s Jemma Morgan explores this issue in her recent blog.

In cold temperatures, animals need to increase their food intake every 1°C that drops below the lower critical temperature (LTC). This puts pressure on food availability.

Dr Whistance provides evidence that trees can help solve these issues. In high temperatures trees canopies help break any solar radiation and capture and store more moisture, leading to a cooling effect. This provides valuable refuge to animals seeking an escape from the heat. In challenging cold conditions, trees help to capture and store warm air underneath their branches, which can sometimes be as much as 6°c warmer than surrounding temperature.

Sheltered refuge is especially valuable during lambing, as newborn lambs must stay warm and dry in their first few hours of life. Without adequate shelter, they risk hypothermia before they can take in vital colostrum, gain energy, and begin to regulate their own body temperature. There are benefits during cold periods too, where grasses grow earlier in the season due to the warm pockets of air. During dry periods, grasses remain green due to the moisture and shade which trees provide. Dr Whistance’s work has also highlighted the benefits of trees in mitigating wind and its influence on ambient temperature.

More farmers are recognising and starting to implement agroforestry to support profitable farming, such as at Longmoor Farm in Dorset.

2- Tree fodder

Trace elements (TE) and plant secondary metabolic (PSM) products form an important part of a herbivore’s diet which directly influence an animals health. Traditionally, tree fodder was a key component of farm animals diet and would provide both of these elements. As access to trees and shrubs has become more restricted in modern day agriculture, these mineral elements have had to be provided through bought in supplements instead.

In one of their studies, Dr Whistance and her team examined mineral content of tree species and found that trees such as willow can provide an important source of cobalt and zinc, particularly valuable for weaned lambs. We have a blog by FCT’s Anthony Ellis on his experiences.

In another of their studies, they also found that the mineral content of stored tree fodder became more available after its storage period, indicating its potential as a stable source of minerals.

As well as animals foraging for the minerals they require, they can self medicate using plants which contain the necessary PSMs. Self selecting behaviour has been studied in goats and sheep and has revealed that those with high worm burdens will seek out leaves with high amounts of tannins to reduce their internal parasites. Certain trees contain high levels of condensed tannins which make them valuable resources for livestock.

Herbal leys provide tannins and trace elements but trees have an advantage due to their larger and deeper root systems that allow them to access minerals deep into the soil. As perennial plants, they also have key relationships with mycorrhizal fungi which increases the variety of minerals and has the ability to use biochemistry to access nutrients that pasture plants cannot. For livestock such as chickens and pigs, alongside providing browse, trees in the field can help promote a wider range of food sources including insects, nuts and seeds and fungi, which all encourages natural foraging behaviour.

3. Expressing animal behaviour

The last point to examine from Dr Whistance’s work is the effect trees can have on farm animal behaviour. The ability for an animal to express its natural behaviour is a key but often overlooked component of farm animal welfare and promotion of healthy animals. Similar to climatic stress and nutrient deficiencies, environmental suppression of animal instinct may lead to abnormal behaviour which then contributes to more serious problems further down the line.

Dr Whistance’s work has found that fields with trees allow livestock to express behaviour such as play (including scratching and rubbing against tree trunks) and encourages the natural instinct to seek hiding places for seclusion. These behaviours support the animals when regulating their own physiological and emotional health. Cattle in silviopasture systems show increased social licking by up to 80%, which is almost double compared to solely pasture systems. This promotes greater social cohesion which results in animals that demonstrate less fear and aggression and consequently stress. On a physical level, animals enjoy and benefit from scratching and rubbing themselves against trees and shrubs as it helps to dislodge parasites and seeds and also removes dead skin and hair which can all contribute to complications. Giving the animal the opportunity to manage its own needs in a suitable way can remove the need for intervention from the farmer.

Conclusion

One of the key insights from Dr. Whistance’s work is the vital role that trees and hedgerows play in helping animals to self-regulate, whether through shelter, diet, or behaviour. Her research highlights the importance of managing and using the natural resources available on the farm to support animal well-being. When used wisely, these resources can offer multiple benefits, reducing the need to purchase external inputs and enhancing the overall sustainability of the farm. By enabling both livestock and the wider farm system to make use of natural features, farmers can strengthen the environmental and economic resilience of their operations – just as previous generations did.

It is important to note that tree systems must be carefully designed to suit the specific needs and conditions of each farm. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, and some adjustments may be necessary as the system grows within each farm.

Key Findings

- Trees and hedgerows are valuable on-farm resources, especially for livestock farmers

- They provide environmental benefits and are key to livestock’s physical and emotional health by facilitating access to shelter, nutrition and expression of natural behaviour.

- Tree planting for livestock requires careful planning so the benefits are optimised and the cost/maintenance kept as low as possible

Recent Comments