Carbon accounting is a fast-moving space, and here at FCT, keeping on top of best practices is one of our top priorities. We commission regular external reviews of all our emissions factors to make sure we’re as compliant and up-to-date as possible. And yet even with the best data available, there’s always the possibility of human error (we all do it!) cropping up in a carbon report.

One area we’re particularly keen to address is how to avoid ‘double counting’ when it comes to farming footprints. This refers to counting the same carbon/CO2e in different places, often (but not always) in the same report.

For example, you might record all your freight and logistics fuel use in the ‘Fuels’ section of our Calculator, only to duplicate the entry under the ‘Distribution’ section. This would result in counting the same emissions twice, artificially inflating the total emissions figure.

These errors can be subtle and easy mistakes to make, so it’s worth reading on to find out how to avoid them and embrace best practices.

How is double counting possible?

Our Carbon Calculator has many different emissions factors that you can record, reflecting the wide variety of needs and business profiles in modern farming. Because of the need for informative metrics and KPIs, our Calculator sometimes offers the option to record an emission or offset in more than one section.

You can therefore choose to either record all of the carbon in one section, or to split it out for better insight in your final report. For example, you may want to be able to see the amount of fuel used in farming operations vs. the fuel used in the distribution of goods. Being able to record the carbon in more than one place is crucial to business insight, but it does introduce the risk of error.

If we want to use these informative metrics, then it’s important to be aware of when you might double-count your carbon.

Where in the Calculator might I be double counting?

We’ve listed below some of the most common areas where double counting may occur in our Calculator. For each one we’ve given an example of how it occurs, and the best practice in order to avoid it.

Animal Feeds – Home grown vs. Bought in

If you are growing your own animal feed on-farm, then you don’t need to account for this in the ‘Livestock’ section. To do so would overestimate your emissions. The Livestock section is only for feeds that are specifically bought in.

To avoid the double count: Make sure that anything recorded as a feed in the Livestock section is a bought-in feed. If not, it doesn’t need to be counted there!

Materials vs. Inventory

The Materials section of our Calculator allows you to record a wide variety of items that are used in construction and repair work. Our Inventory section, on the other hand, is there to record larger capital items such as new outbuildings or farm machinery. This difference is key, as any items within the Inventory section will have their carbon impact depreciated over a period of 10 years.

It’s also possible to record your own custom building projects inside the Inventory section. For example, you might choose to record all the materials associated with a new outbuilding. This might be done so that you can achieve a more precise footprint for a non-standard construction.

Where materials are purchased for running or regular repairs of existing installations, record these in the Materials section.

To avoid the double count: Make sure you’re not recording any custom-build projects in both Materials and Inventory. They only need to be recorded in one of these sections!

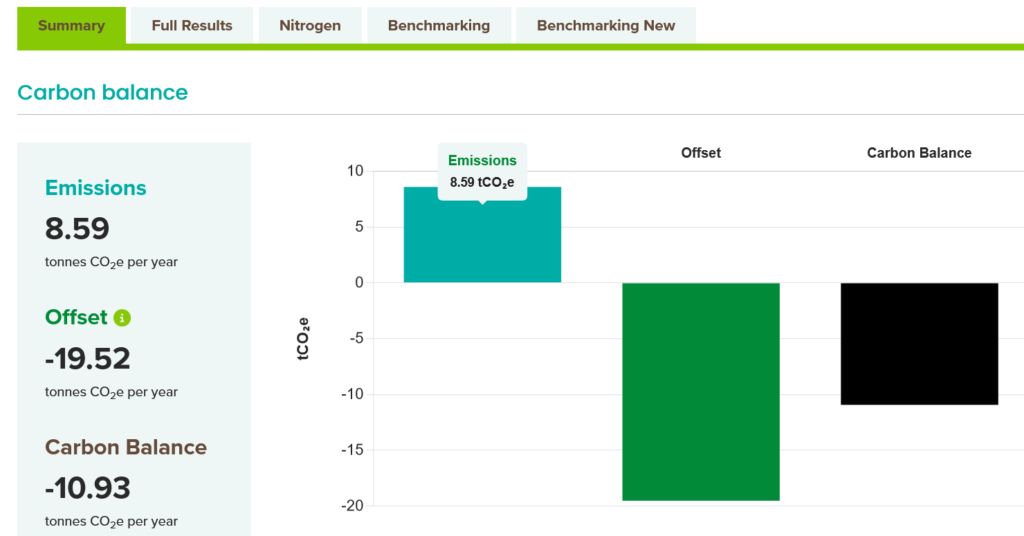

Sequestration – Double Counting Offsets

If you have previously sold any carbon offsets, for example through soil organic carbon sequestration, then you should not count the offset in your report. To do so would be an example of double counting as the benefits are no longer attributable to your farm business.

To avoid the double count: Make sure you’re only recording potential sequestration that hasn’t been sold or accounted for elsewhere.

Sequestration – Double Counting potential sequestration

If you have entered an area of land under the sequestration option: “Soil Organic Matter” or “Soil Organic Carbon” (using information from soil sampling), you should not also enter those areas of land under other sequestration options (such as Countryside Stewardship Schemes, even if the land is receiving payment for that scheme). Direct soil sampling is preferable in this scenario. Similarly, whilst in practice you can “stack” the payments you receive from stewardship grants, you must only enter areas of land for sequestration under one potential sequestration option (so if “My field” is 5ha, I can enter soil sampling data from those 5ha OR the fact that they are under a Countryside Stewardship Scheme).

To avoid the double count: Include each field area under only one potential ‘Sequestration’ option.

Fuel Use – Distribution vs. Farming Operations

If you want to split out your fuel use into distribution and farming operations, you have the option to record these separately. Any farm fuel use such as red diesel can be recorded under ‘Fuels’. Any fuel used in moving goods can be put under ‘Distribution’.

To avoid the double count: We recommend splitting out fuel use between ‘Fuels’ (i.e. farm operations) and ‘Distribution’.

The Exceptions

As with all good rules, there are some apparent exceptions:

- you CAN add multiple crops that have been grown on the same area of land in the same year (but only include those that have been harvested or terminated within the reporting period).

Recent Comments