An overview of GWP* and the Farm Carbon Toolkit position on alternative metrics for carbon footprinting.

Methane plays a crucial role in climate change, but accurately measuring its impact has long been a challenge. The most commonly used metric for measuring its impact is GWP100, which calculates its warming effect over a 100-year period. However, GWP100 does not fully reflect the gas’s short-lived nature in the atmosphere, potentially misrepresenting its impact compared to other greenhouse gases.

As a result, an alternative approach, known as GWP*, has been developed to address the challenges of measuring methane using GWP100, while offering a more dynamic picture of the gas’s real-time warming impact. At Farm Carbon Toolkit, we recognise the growing discussion around methane reporting and the potential benefits – as well as limitations – of using GWP*. This article explores the differences between GWP100 and GWP*, their implications for farmers, and how GWP* could be responsibly integrated into emissions reporting.

What is Global Warming Potential and How is it Measured?

Global Warming Potential is a measure used to compare the impact of different greenhouse gases on atmospheric warming over a specific period, relative to carbon dioxide. Since each greenhouse gas varies in how much heat it traps and how long it remains in the atmosphere, Global Warming Potential provides a standardised way to assess their contribution to climate change.

Carbon dioxide is used as the baseline because it is the most abundant greenhouse gas. GWP100 is the most widely used version of the Global Warming Potential metric, measuring the average warming potential of a gas over 100 years. This approach is the international standard used in greenhouse gas reporting, including in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) guidelines.

Carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere for the longest – up to a thousand years – but has the smallest warming impact of greenhouse gases and a GWP100 score of 1. However, as it is the most abundant and long-lasting GHG, this does not diminish its warming impact. In comparison, other greenhouse gases, such as methane and nitrous oxide, have significantly higher warming effects over shorter timeframes. The GWP100 for nitrous oxide is 265, meaning that one tonne of nitrous oxide causes the same amount of warming as 265 tonnes of carbon dioxide over a 100-year period. This is calculated with consideration for nitrous oxide’s 100-150 year lifespan.

GWP100 Limitations

While GWP100 is a useful tool for measuring the impact of different greenhouse gases, it has limitations. For gases like nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide, which persist in the atmosphere for hundreds or thousands of years respectively, GWP100 works well, providing an accurate comparison of their long-term warming effects. However, for methane – a potent greenhouse gas that remains in the atmosphere for only about 12 years – GWP100 fails to capture its true impact on climate change. Methane’s potency is not fully reflected when assessed over a 100-year period. While it persists for a short time, it traps heat much more effectively than carbon dioxide, significantly contributing to warming during that period.

As the science of climate change and greenhouse gas emissions evolves, it’s clear that alternative metrics will be necessary to provide a more accurate picture of methane’s role in climate change and to guide effective mitigation strategies.

GWP*: A New – but Incomplete – Approach

One such alternative metric is GWP*, which has been developed to better reflect methane’s global warming impact. Unlike standard GWP100, which assumes that emissions remain constant over time, GWP* accounts for methane’s faster breakdown in the atmosphere. As a result, GWP* can provide a clearer picture of how changes in methane emissions affect the climate in real-time, rather than assuming the gas has the same long-term impact as carbon dioxide.

Given the limitations of GWP100 in accurately reflecting methane’s warming impact, it may seem logical to switch entirely to GWP*. However, GWP* cannot be used to create a carbon footprint on its own.

One of the main reasons for this is that GWP* is not yet an internationally recognised reporting metric. While it is gaining traction in climate science discussions, it has not been formally adopted by key regulatory bodies such as the IPCC.

A further challenge of using GWP* alone is that it can cause confusion for emissions reduction efforts, especially at the farm level. GWP* measures the relative change in methane emissions over time, rather than just the total emissions. This means that small, natural variations in factors like herd size or crop activity can cause large fluctuations in carbon footprints from one year to the next. For example, a change in management practices can result in higher methane emissions, causing a spike in the carbon footprint. Conversely, a reduction in emissions, for example, from improving the efficiency of livestock production, has a greater immediate impact on reducing a farm’s reported warming contribution. These fluctuations can make emissions appear inconsistent, even if the farm’s overall environmental impact is improving. The danger is that such variability can make it harder to track long-term progress and could undermine efforts to reduce emissions.

Because of this, GWP* is most effective when applied over longer timescales and at larger scales, such as national-level carbon accounting over several decades. At this level, GWP* helps provide a more accurate picture of methane’s true warming potential, without the misleading volatility that occurs when used for annual farm-level reporting.

For these reasons, while GWP* offers important insights into methane’s role in climate change, it should be used alongside existing GWP100 calculations rather than replacing them entirely. Employing GWP* in a way that accounts for long-term trends, rather than short-term variability, ensures that methane’s impact is assessed more accurately while still maintaining consistency in emissions reporting.

How Could GWP* be Applied to Farms?

In theory, GWP* could be used alongside GWP100 to provide a more accurate representation of a farm’s long-term methane emissions. However, applying GWP* in a practical and reliable way would require specific data and methodologies that are still under development.

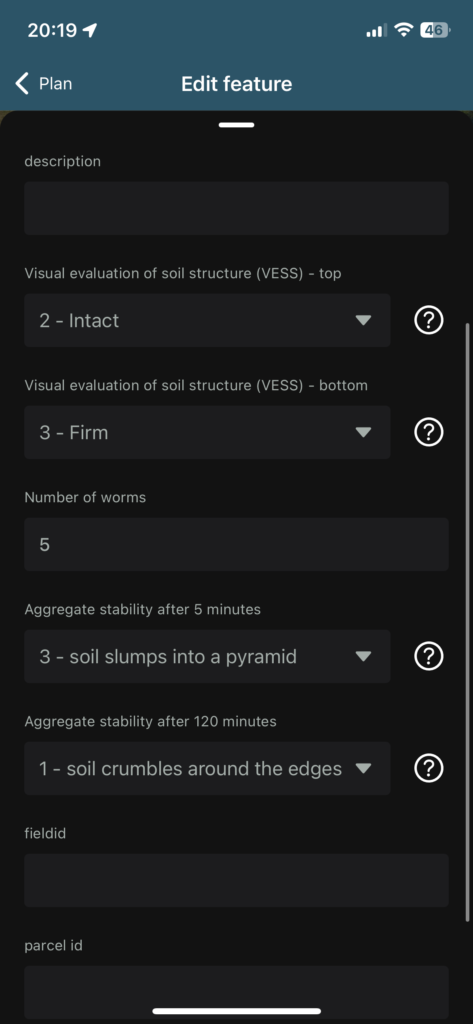

To integrate GWP* into farm-level carbon footprinting, methane emissions would first need to be separated from other greenhouse gases in the emissions inventory and treated differently. Unlike GWP100, which applies a single factor to all emissions, GWP* relies on understanding the historical emissions data of methane — typically covering at least 20 years. This historical data is essential because GWP* calculates methane’s impact based on its rate of change over time, rather than treating all emissions as having an equal long-term effect.

For an annual carbon report, the current year’s methane emissions would be adjusted based on the historical trend in emissions and a GWP* constant that scales the calculation to methane’s lifespan. However, this GWP* constant is still under development, with debates over the extent to which methane should be scaled, and, as such, has not yet been universally accepted. Once adjusted, the GWP* methane value would then be multiplied by the GWP100 emissions factor to integrate it into the overall farm footprint.

Essentially, this approach modifies a farm’s yearly methane emissions based on historical trends, scaling them to better reflect methane’s atmospheric lifespan before incorporating them into a GWP100-based report. While this suggests that GWP* could theoretically be applied in annual farm reports, it requires two critical components: comprehensive legacy data on methane emissions and an agreed-upon GWP calculation constant – both of which are still being refined by climate scientists.

The use of GWP* will show the most dramatic impact on the carbon footprint of extensive ruminant livestock farmers, where a high proportion of their emissions come from enteric methane emissions. Currently, for these types of systems, under the current footprint methodology, there remain limited management options for mitigation of emissions other than reducing stock numbers.

Until these foundational elements are fully developed and standardised, GWP* cannot yet be seamlessly implemented into farm carbon footprinting. However, as research continues and reporting frameworks evolve, there may be future opportunities for farms to integrate GWP* into their emissions assessments in a way that balances accuracy with practical usability.

Distinguishing Between Methane Sources

While GWP* offers a more nuanced way to assess the impact of short-lived greenhouse gases like methane, it is equally important to differentiate between biogenic and anthropogenic methane sources when applying this metric.

Biogenic methane – produced naturally through biological processes such as enteric fermentation in livestock, wetlands, and peatlands – should be adjusted using GWP*. This is because biogenic methane is broken down in the atmosphere at roughly the same rate that it is produced, meaning that when emissions remain stable, there is no net increase in atmospheric methane levels. This natural balance is an essential factor in ensuring that methane’s impact is not overstated when using GWP100.

Anthropogenic methane, on the other hand, originates from human activities such as fossil fuel extraction, waste management, and slurry management. Unlike stable biogenic methane sources, anthropogenic sources add to the atmospheric methane stockpile, meaning these emissions accumulate over time rather than cycling naturally. Because of this, applying a GWP* adjustment to anthropogenic methane could underestimate its long-term climate impact, as it does not break down at the same rate that it is emitted.

Another key consideration is that as anthropogenic methane breaks down, it eventually converts into carbon dioxide, contributing to the long-term stockpile in the atmosphere. Since carbon dioxide persists for thousands of years, this means that anthropogenic methane has a dual impact – it plays a role in short-term warming as methane and then adds to long-term warming through its carbon dioxide byproduct.

These distinctions raise important questions about how GWP* should be applied. Should emissions from degraded peat bogs or residue burning be classified as natural or human-driven? Should increasing herd sizes in agriculture be considered an anthropogenic influence? The way these questions are answered will determine which methane emissions qualify for GWP* adjustments and which should be assessed using traditional GWP100 methods.

To ensure accurate and fair carbon footprint assessments, clear guidelines on how to apply GWP* in different contexts are essential. As the science behind methane accounting evolves, so too must the frameworks that determine when and how GWP* is used in emissions reporting.

Looking Ahead: The Role of GWP* in Farm Carbon Reporting

The debate around GWP* reflects its potential to improve how we account for methane emissions, particularly for livestock systems that feel misrepresented by GWP100. While it offers a more realistic view of methane’s short-term climate impact, its sensitivity to year-on-year changes can create volatility in farm-level reporting and complicate efforts to track progress reliably.

There is also a risk that GWP* could be misused, allowing businesses to claim emissions reductions without making genuine changes, or pressuring farmers into quick fixes like reducing herd sizes. To avoid these outcomes, any use of GWP* must be transparent, grounded in science, and applied fairly across all sectors. Done well, it could become a valuable tool – alongside GWP100 – for building a more accurate and trusted approach to agricultural carbon footprinting.

At Farm Carbon Toolkit, we remain committed to exploring how GWP* can be integrated responsibly into emissions reporting, ensuring that any changes reflect both scientific accuracy and practical fairness for farmers. We are exploring how GWP* can be appropriately implemented alongside the current GWP100 reports as part of a dual reporting system. With this in mind, we recommend continuing to produce reports using GWP100 now, as these will provide a valuable baseline to support dual reporting in the future. Given the significant impact of timespan on GWP* data, we are considering solutions based on multi-year reporting to improve accuracy and consistency.

As research progresses and reporting frameworks evolve, clear guidance and safeguards will be essential in ensuring GWP* supports effective, fair and transparent carbon reporting across the farming sector.

Craig Blyth-Moore is a sustainability communications professional with over a decade of experience turning complex environmental issues into clear, compelling narratives. He has written extensively on energy efficiency, renewable energy, the energy transition and sustainable logistics, helping organisations communicate their sustainability strategies with credibility and impact.

Craig holds an MSc in Environmental Sustainability and brings both subject matter expertise and strategic insight to his work. His writing has appeared on leading global platforms including Economist Impact and the World Economic Forum, helping to inform and inspire meaningful climate action.

Recent Comments